Financial Predators Take Advantage of Refugees by Dangling Federal Benefits, by Omar Khan

Refugees are being taken advantage of by unscrupulous finance companies and salespeople who are using a family’s interest in their child’s education, combined with federal government letters of encouragement and federal benefits, to enroll refugees in savings programs with a high risk of financial loss.

Background

Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs) are incentive-based, tax-advantaged savings plans that people, traditionally parents, can use to save money for children’s post-secondary education (PSE). The funds become available when the child begins attending a post-secondary institution. These plans can be opened at most financial institutions and range from basic fee-free bank plans to high-fee group plans administered by RESP-focused financial institutions. As of the end of 2015, RESP assets in all financial institutions totaled around $47 billion.

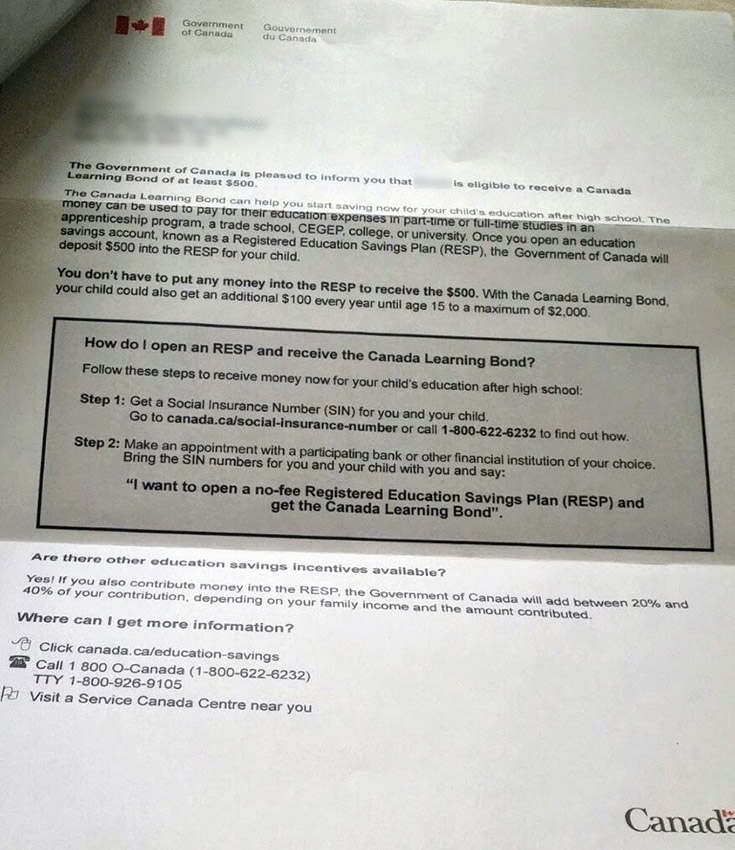

One incentive for low-income families to use RESPs is the Canada Learning Bond (CLB). The federal government writes that the CLB

is available for children from low-income families born in 2004 or later. This education savings incentive consists of an initial payment of $500 plus $100 for each year of eligibility, up to age 15, for a maximum of $2,000. No personal contribution is required to receive the CLB.

Thus, a low-income family can access up to $2,000 of money for their child’s post-secondary education just by opening an RESP account at a bank or financial institution. As of the end of 2015, 33%, or approximately 800,000 of the 2.5 million CLB eligible children have signed up. Thus, 67% of CLB-eligible children have not been enrolled in an RESP, and are not accessing this funding.

The federal government is so keen on the CLB’s ability to make post-secondary education more accessible that at the time of this writing in January 2018, they have a Call for Concepts to Increase awareness and take-up of the Canada Learning Bond, with a focus on reaching “underrepresented, hard-to-reach and vulnerable segments of the population who may face challenges in accessing the CLB.” The reason for this reach is clear:

The primary complaint about RESPs and the associated savings grants as a means of financing PSE is that their benefits accrue disproportionately to wealthier families. In 2014, according to Statistics Canada, 68 percent of parents with children under the age of 18 and with annual incomes over $120,000 had an RESP; this compares with 46 percent of those with incomes between $32,000 and $55,000, and only 37 percent of those with incomes of less than $32,000. (from the Institute for Research on Public Policy)

Refugees

It is important to note that RESPs are open to any person with a Social Insurance Number (SIN) — this includes refugees who have received permanent residence, as well as refugee claimants, who can obtain a temporary SIN. Whether you have a SIN or not, it appears that if you received the Canada Child Benefit for your children, and yet didn’t have an RESP for those children (a large number of refugees, though not claimants, fall into this category), you received the following letter:

I, along with many volunteers, help Government Assisted Refugee (GAR) families settle in Canada. The majority of families I work with are Syrian. Concerning the above letter, almost every family I know asked, “What is this?” because no translation was provided. Often families would simply ignore the letters, not knowing what to do with them. This is not a small issue: with around 50,000 Syrian refugees granted entrance to Canada between November 2015 and November 2017, and estimates of around 50% of these refugees being 14 and under, the number of Syrian refugees who are eligible for the CLB is on the order of the number of children eligible in all of Newfoundland and Labrador (approximate 32,000).

Enter the Financial Predators

The CLB, and RESPs, came to my attention when a Syrian newcomer refugee family told me they were getting calls and visits from an Arabic-speaking person asking them to sign up for an RESP plan for each of their kids. The family was interested: they want their kids to go to college or university and succeed in Canada. I called this person and learned that they were a salesperson for a group RESP provider. I tried to determine fees and commission, but she told me she couldn’t share that information with me and that I should go to the website. After much research, I learned that the plan required, at minimum, hundreds of dollars of monthly contributions from the family, and the fees were onerous. I told the family that they should instead just go to their bank, as suggested by the federal government letter, which charges no fees and requires no minimum monthly contributions.

A few months later, the family said they were getting the same calls and visits, and that many families in the area had signed up for an RESP with the same questionable company. The family asked me to share my concerns with the other families. I met with a few of these families and explained my concerns about the fee structure, and the possibility of losing much of their money if they had to cancel to withdraw some of their contributed money, a not uncommon situation for families with little savings. The families were alarmed, and told me that they thought the Arabic-speaking person worked for the government, because she kept mentioning the government providing money to their kids. When I told them that she was a salesperson, and I explained how her commission structure worked, they became extremely concerned. I learned that the following day a group of men from the families had filled a few cars and driven to the headquarters of the financial company, demanding that their children be removed from the plan. The company would not accept this request, because the fine print on cancellation stated that all parties to an agreement (which in every case was the father AND mother) had to consent to cancellation, and the mothers were not present. Some of the families then contacted me, and together we were able to produce the appropriate cancellation letters to remove some families from the plans. Others were not so lucky — they had already passed the 60 day cancellation mark. After this experience, I told one family that had cancelled that while this was a bad experience, the RESP benefits for their children were clear and they should go and sign up at their bank. The father told me he was very concerned about the whole RESP program, and he wouldn’t sign up.

I have explained this situation to the Ontario Securities Commission and they have indicated that they are investigating. Furthermore, groups like the Omega Foundation are working to enroll more low-income families in no-fee RESP plans via programs like SmartSaver.

This story raises a number of questions and concerns:

- How can newcomers meaningfully consent to any program when they only have access to an English description of the program and a salesperson working on commission who has no incentive to adequately explain the fee structure? When asked, no newcomer was able to describe any fee structure shared with them.

- While this unethical behaviour is not isolated to refugees (see, for example, other stories of surprised consumers, online forum complaints, criminal actions by RESP salespeople and disciplinary measures taken by the Ontario Securities Commission against one group RESP provider), refugees, especially GARs, typically have: trust in government workers and programs, low language proficiency in English or French for months to years after arrival, little access to or knowledge concerning who here in Canada can help them make financial decisions, and, finally, few avenues of recourse when things go wrong. These are ideal candidates for unethical financial institutions that build upon the seemingly good government RESP program

- Are households with stable incomes, savvy investors and financial institutions the only guaranteed winners with the RESP program? Can it be modified to avoid exorbitant fees and penalties, especially for vulnerable populations like refugees?

Policy Recommendations

The many Syrian newcomer refugee families I know want their kids to attend college or university. They see this path as a good one for their kids. This aspiration is supported by research with wider groups of refugee youth in Toronto. Clearly, the federal government wants to support this aspiration. However, the federal government needs to think about how they can adapt their more general programs to serve this population, and not inadvertently lead some people into potential financial jeopardy.

If the government truly wants to invest in the educational potential of low-income children, then they need to ensure that RESPs are provided only through regulated financial institutions at little or no cost to account holders. This can be done through administrative or regulatory changes to the program. For example, the government could by default universally enroll all CLB eligible children (ie children in low-income families) into a federal savings plan administered by the federal government. Recently, the Institute on Assets and Social Policy at Brandeis University studied Children’s Savings Accounts, an American structure similar to RESPs, and found a number of mechanisms that make RESP-like plans more clearly beneficial to low income families, and automatic enrollment is chief among them.

The policy levers are there. The federal government needs to pull some of them to make RESPs safe and beneficial for all families, especially refugees.

Omar Khan is a computer scientist and sometimes artist. For two years he has been working as a refugee advocate in Toronto. He serves in an advisory role for Together Project, a project of Tides Canada, has worked on multiple refugee education initiatives, and is pushing the Ontario Government to change its driver license policies for refugees.